Revolutionizing Oncology With CAR T-Cell Therapy

How nurses can serve on the front line of CAR T-cell therapy to ensure patients have the best care.

Approximately every 3 minutes, 1 person in the United States is diagnosed with a blood cancer, according to the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.1 Despite standard treatments and advancing research, the statistical significance of relapse among patients with hematological cancers continues to validate the need for more promising treatments. One area in which there is growing hope: chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

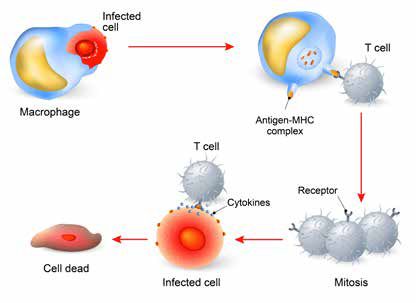

Over the past century, researchers have investigated innovative ways to treat cancer using multiple modalities. New classes of agents known as immunotherapies, which are treatments that use the body’s immune system to fight cancer, are the latest developments in the field of oncology. These include checkpoint inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, oncolytic viral therapies, and CAR T-cell therapy. 2 These treatment modalities have either been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or are being studied further under clinical trials. One major advantage of using immunotherapy to fight cancer is the ability of these drugs to differentiate self from nonself, given their receptor specificity.

CAR T-cell therapy has become one of the most promising new treatments for hematologic malignancies, with long-term advances minimizing the risk for relapse. In August, the FDA issued a historic approval of the first CAR T-cell therapy authorizing the use of tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) for the treatment of patients up to 25 years of age with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia that is refractory or in second or later relapse. The primary efficacy analysis was based on phase II results from CCTL019B2202 (B2202), a single-arm, international trial of 63 patients who received a single dose of tisagenlecleucel. Overall remission rate was 82.5% in treated subjects. Forty patients (63%) had complete remission and 12 (19%) had complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery.

CAR T-cell therapy aims to control cancer developent through modification of the patient’s immune system. However, despite its positive outcomes, the therapy comes with risk for complications, signifying the need for oncology nurses to possess the clinical expertise to manage the care of patients receiving these treatments and educate their patients and families throughout the continuum of care.

THE ROLE OF THE ONCOLOGY NURSE

When patients are undergoing CAR T-cell therapy, it is important for their nurses to have the knowledge and skills to care for them throughout the plan of care. This should include the apheresis process, conditioning therapy, T-cell infusion, and the risk of post complications. In addition, nurses should ensure that patients and their loved ones are active participants in their care. Caregivers are essential because they can recognize subtle changes in the patient that may not be noticed by healthcare providers.

When a patient is preparing to begin treatment, their T cells are collected through apheresis. The cells are then sent to a laboratory to be genetically modified to produce CARs on their surface.

As the T cells are stored in the lab, they expand, resulting in millions of cells.1 These cells then are frozen until they are ready to be infused back into the patient.

CONDITIONING THERAPY AND STEM CELL INFUSION

Prior to the cell infusion, patients with cancer will receive chemotherapy. Upon completion of the chemo treatment, the T cells are infused back into the patient either in the inpatient or outpatient setting. During the infusion, the nurse is responsible for verification of the T-cell dose with the stem cell technician and another licensed practitioner; frequent vital signs monitoring (temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and pain rating), based on the institutional standards; monitoring the patient for any significant changes in vital signs or signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis; and accurate documentation of the infusion and/or any adverse events (AEs) during the infusion.

MANAGING ADVERSE EVENTS

Over the next 2 weeks following infusion, the patient should be closely monitored for any AEs related to the infusion and their stem cell recovery. CAR T-cell therapy can cause severe, and sometimes fatal, AEs. The 3 most concerning AEs include cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurologic toxicity, and tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). Symptom severity is relative to the disease burden of the patient prior to treatment. By recognizing early signs of AEs and collaborating with the multidisciplinary team, nurses can optimize patient survival.

CRS is a serious toxicity, ranging from mild to life-threatening, which occurs when there is activation of T cells that proliferate and lead to an inflammatory response caused by interleukin 6 (IL-6). The nurse must monitor the following labs and clinical data as they may be closely elevated:

• Low-grade (38°C/100.4°F) to high-grade (40°C/104°F) fever

• Hypotension

• Tachycardia

• Capillary leak syndrome

• Acute respiratory distress syndrome

• Lactate dehydrogenase

• C-reactive protein

• Liver enzymes

• Creatinine

• Partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time/ international normalized ratio

• Ferritin

The antidote for CRS is tocilizumab (Actemra), an IL-6 receptor antagonist, which was approved by the FDA on the same day as tisagenlecleucel. This is given to reverse the severi-ty of the cytokine release symptoms and prevent binding to the CD19 receptor.3 Patients are premedicated with Tylenol and Benadryl to minimize risk for anaphylaxis and any infusion reactions. Once tocilizumab is administered, symptoms such as fever, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation return to baseline within 24 to 48 hours. By assessing vital signs frequently, the nurse can intervene appropriately to minimize morbidity.

Methylprednisolone should not be given as a first-line treatment for CRS because the mechanism of action for this drug blocks the activation of T cells, which negates the purpose of the CAR T-cell infusion. Patients and caregivers should be made aware of this in case they have to receive care in another setting; for instance, if they are seen in the emergency department and healthcare providers are not aware that the patient has received CAR T-cell treatment.

IL-6 deposits in the brain after crossing the blood—brain barrier, causing neurological complications Some patients may experience somnolence, confusion, agitation, tremors, and seizures. If this occurs, nurses should do the following: perform neurological assessments routinely and as needed; conduct frequent rounding to ensure patient safety; communicate promptly with the medical team to effectively treat their symptoms; perform diagnostic tests, which may include computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and lumbar punctures; and, potentially, administer antipsychotic medications, such as the anticonvulsant, levetiracetam (Keppra), to minimize the development of seizures.

TLS is a condition caused by the rapid destruction of tumor cells, which leads to hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyperuricemia, and hypocalcemia. Patients that present with a high tumor burden are at risk for TLS. Early recognition by the nurse is key in prevention and management. This may include administering isotonic intravenous fluids to maintain the urine output to 30ml/hour; daily allopurinol to minimize the risk for kidney failure, given the destruction of uric acid; monitoring electrolytes and kidney function; and temporary dialysis.

MOVING FORWARD

As CAR T-cell therapy advances in the treatment of cancer, hands-on training prior to caring for these patients is crucial. These patients are at risk for morbidity and mortality as a result of unrecognized clinical presentation of symptoms. Therefore, nurses must learn about and be aware of early symptoms, AEs, and other toxicities.

Long-term side effects are still unknown given this treatment’s early inception, which validates the need for nurses to report any significant changes from the patient’s baseline status. In time, there will be opportunities for long-term studies to be conducted that will provide better guidance and understanding of the treatment in the front-line setting.

Stephanie Jackson is an oncology clinical nurse specialist at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles. Her clinical expertise is in adult hematology and stem cell transplants.

References1. Facts and Statistics. Leukemia & Lymphoma Society website. https://www.lls.org/http%3A/llsorg.prod.acquia-sites.com/facts-and-statistics/facts-and-statistics-overview/facts-and-statistics. Accessed July 23, 2017.2. Bayer V, Amaya B, Baniewicz D, Callahan C, Marsha L, McCoy A. Cancer immunotherapy: an evidence based overview and implications for practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(2):13-21. doi: 10.1188/17.CJON.S2.13-21.3. Smith L, Venella K. Cytokine release syndrome: Inpatient care for side effects of CAR T-cell therapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(2):29-34. doi: 10.1188/17.CJON.S2.29-34.

Innovative Program Reduces Nurse Turnover and Fosters Development

Published: September 12th 2024 | Updated: September 12th 2024The US Oncology Network (The Network) has developed one of the most comprehensive programs in the nation to support the professional development and retention of new oncology nurses.