Perspectives on Best Practices in Caring for Patients With Pancreatic Cancer and Cholangiocarcinoma

Patients with unresectable pancreatic cancers and cholangiocarcinoma face poor prognoses, but systemic treatment continues to evolve.

No one understands the saying “cancer sucks” better than oncology nurses and their patients. For patients who receive a diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma, the words do not seem to go far enough. However, there are certain systemic treatments offering some hope for patients with unresectable disease.

In 2023, an estimated 64,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer will be diagnosed in the United States and 50,550 lives will be lost to the disease, making it the third-leading cause of cancer-related death. Even when the disease is identified early, treating it is still a challenge; for those with localized disease, the 5-year relative survival rate is close to 45%, and for those who have advanced-stage cancer, the rate is approximately 3%. For all stages combined, it is 12%.1

Cholangiocarcinoma occurs less frequently than pancreatic cancer, with approximately 10,000 new cases diagnosed annually in the United States. For localized, regional, and distant disease, the 5-year relative survival rates sit at 9% for intrahepatic tumors and 10% for extrahepatic tumors.1

Unlike therapies for some malignant tumors, treatment trajectories for pancreatic adenocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma are not very straightforward. To provide a better understanding of best practices for these cancers, Oncology Nursing News spoke with 4 oncology nurses who are well versed in this arena.

Molecular Testing and Liquid Biopsy

Molecular testing is recommended for most patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma.2 Testing has a 2-fold purpose. By identifying germline or somatic pathogenic variations, patients will have a better understanding of future cancer risk for themselves and their family members, and treatment can be individualized accordingly.3 For example, patients with FGFR2 mutations may be prescribed oral chemotherapy (infigratinib [Truseltiq], pemigatinib [Pemazyre] or futibatinib [Lytgobi]), and ivosidenib (Tibsovo) is indicated for patients with tumors with IDH1 mutations.

Mutations for pancreatic cancer include BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2.2 More than half of patients with cholangiocarcinoma have at least one of many known targetable mutations, such as IDH, FGFR, and NTRK.

“Identifying tumor biomarkers means more optimal treatment,” Kristin Ferguson, DNP, RN, OCN, said. Ferguson is a nurse administrator for Lombardi Cancer Center at Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, in Washington D.C., a board member with the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS), and a volunteer fundraiser for the Pancreatic Action Network (PanCan). Ferguson’s mother received a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in 2017 and died 2 years later.

Ferguson’s personal experience with the disease has increased her understanding of the challenges faced by those receiving a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and informed her care at the bedside. “PanCan’s Know Your Tumor [program] offers valuable information about targeted therapy for providers and their patients,” she noted.

There are numerous methods of collecting pathology specimens,

including diagnostic surgery, core biopsy, fine needle aspiration, and brushings of the bile or pancreatic duct.4 Results may take weeks or even months to complete. “Having this information ahead of time and adding it to the patient’s treatment toolbox expedites future treatment and helps clinicians monitor disease progression,” Ferguson said.

It is not uncommon, however, to have insufficient tissue amounts available formolecular testing.5 “Fine-needle aspiration may not yield enough tissue. In these cases, liquid biopsy is an alternative,” Kelley Rone, DNP, RN, AGNP-C, said. Rone works in the Gastroenterology Oncology Clinic at Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona, and has the following advice for nurses: “Look at the patient’s chart to see [whether] molecular profiling has been done. If not, ask the oncologist about it. It’s a fair question. There is still some debate about the value of testing [because] it may or may not aid in treatment decisions. It is well known, however, that targeted treatment works much better.”

“Next-generation sequencing, or NGS—both via tissue or liquid biopsy—is approved by Medicare for advanced stage [stage III-IV] solid tumors, including pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma, and most commercial insurers also cover the cost of this testing,” Jennifer Wild, MSN, BSN, RN, said. “The potential benefit of testing outweighs the risk of not testing.”

Wild, who works at the University of California, San Francisco Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology Clinic and is a nursing advisory board member with the Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation, added that “financial toxicity used to be a great deterrent to folks seeking NGS testing, but we are working on bridging that gap for patients regardless of socioeconomic status The main barrier now is about knowing that it’s out there. The Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation’s nursing advisory board strongly recommends that all cholangiocarcinoma patients ask their oncologist about NGS testing at the earliest opportunity.”

Treatment Decisions for Pancreatic Cancer

Surgery is the only potentially curative treatment for patients with pancreatic cancer. Unfortunately, fewer than 20% of pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumors are resectable. Decisions about tumor resectability should be presented for discussion to a multidisciplinary board at a high-volume center.2

“Surgery for pancreatic cancer depends on multiple factors, including tumor location and blood vessel involvement,” Liz Prechtel Dunphy, DNP, CRNP, ANP-BC, AOCN, remarked. Dunphy, a nurse practitioner at Penn Presbyterian’s Abramson Cancer Center, in Philadelphia, has worked with gastrointestinal (GI) malignant tumors for many years. “It’s important to look at the patient from different modality viewpoints to determine best treatment,” she added.

Pancreatoduodenectomy, also known as Whipple procedure, is the gold standard for resectable tumors found in the head of the pancreas. This is a complex operation involving the GI tract in which the head of the pancreas, gallbladder, duodenum, and part of the stomach are removed and remaining portions are reconnected. Complications can be life-threatening. Infection is the most serious complication, and delayed gastric emptying is the most common complication.

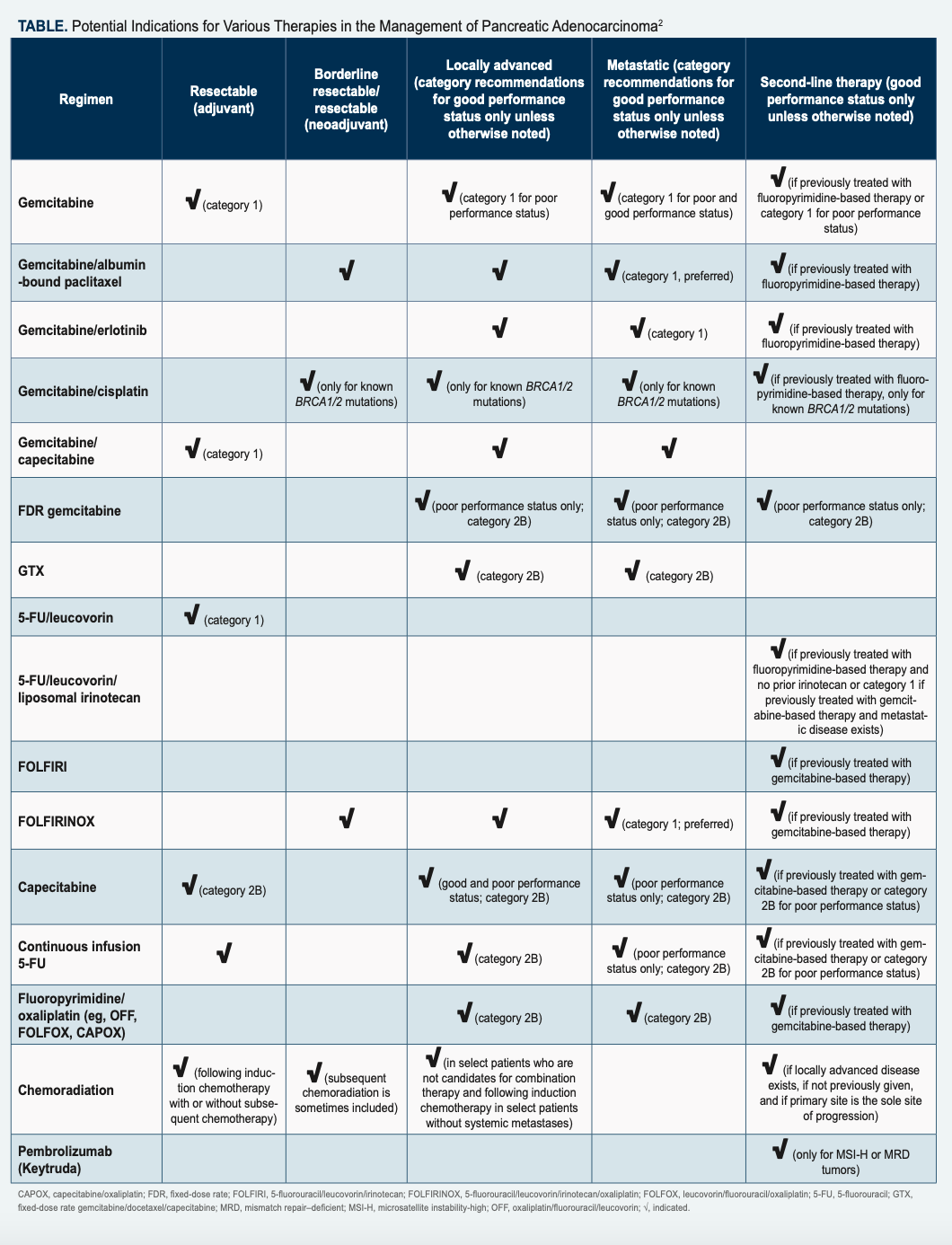

Other surgeries include distal and complete pancreatectomy. Postsurgical recurrence rates are high. Palliative surgery may be helpful for symptom relief with unresectable tumors. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation may be given to shrink borderline resectable tumors and help patients qualify for surgical candidacy (Table).2

Nurses play a vital role in treatment discussions with patients, Ferguson explained. “Patients may wonder [whether] they should go through treatment. Nurses can help patients understand the benefits of treatment, such as slowing tumor growth, reducing severity of adverse effects [AEs], and prolonging life. Patients should also be referred to reputable sources of information such as PanCAN and the NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network].”

Chemotherapy may be the only form of therapy for some patients with metastatic disease and is tailored to a patient’s performance status, comorbidities, and symptoms. “For patients with metastatic disease who are otherwise healthy, our first and ideal recommendation would be participation in a clinical trial,” Dunphy noted. “If that is not an option, chemotherapy would be indicated.”

In most cases, treatment with modified FOLFIRINOX (mFOLFIRINOX; 5-fluorouracil [5FU], irinotecan, oxaliplatin, leucovorin), is standard therapy for patients but depends on their performance status, because a fair number of AEs may occur. mFOLFIRINOX is given every 2 weeks. “Part of the treatment is given in clinic, then patients go home with low-dose 5FU running for 46 hours. If a home infusion nurse is available, they will disconnect the infusion. If not, patients return to clinic for disconnection,” Dunphy said.

Patients with poor performance status who have progressive disease or did not tolerate FOLFIRINOX are given gemcitabine with albumin-bound paclitaxel. For tolerance reasons, they may receive gemcitabine alone, although the doublet if preferred. Dunphy added, “Another reason to use the gemcitabine regimen would be allergy to oxaliplatin. Either regimen may be used as neoadjuvant treatment. mFOLFIRINOX is preferred and may require further dose modifications based on patient’s tolerance to the medications.” Treatment considerations are based on how fit the patient is and medication side effects.

“This is a complex arena for patients,” Rone added. “I feel like we don’t do a good enough job preparing them. If you tell them everything, they are terrified. You have to consider how much information they can process at one time.”

Rone shared the story of a fit 80-year-old patient with borderline resectable cancer, diabetes, and a biliary stent. The patient received all necessary information prior to treatment but did not show up for her first chemotherapy appointment. It turned out that the patient was overwhelmed and afraid. When this happens, it’s important for nurses to listen and remind patients that chemotherapy is more tolerable than it used to be and management of AEs has greatly improved.

Treatment Decisions for Cholangiocarcinoma

As with pancreatic cancer, surgery is the only potentially curative treatment

for patients with cholangiocarcinoma.6 Similarly, resectability should be assessed by multidisciplinary review, including surgeons and radiologists experienced with this rare disease. Most patients will not be candidates for surgery because of advanced stage at diagnosis. For resectable tumors, the type of surgery is based on where they are located, and the relapse rate following surgery is 60%. Six months of adjuvant chemotherapy is therefore recommended.7 Liver transplantation for unresectable cancer may be an option, although many transplant centers do not accept patients with cholangiocarcinoma.6

Cholangiocarcinoma resection is complicated and requires great skill. Open or laparoscopic resection, wedge resection, partial or complete hepatectomy, or Whipple procedure may be indicated.8 Complications are similar to those associ- ated with pancreatic resection and include bleeding, infection, and digestive/nutri- tional problems. The standard of care for advanced cholangiocarcinoma now includes chemotherapy (gemcitabine and cisplatin) plus immunotherapy, with the recent FDA approval of durvalumab (Imfinzi).9 “The response rate is longer and people live a bit longer [with this treatment],” Wild noted. “This 3-pronged approach is given as a standard 21-day cycle. Patients receive all 3 agents on day 1, chemotherapy on day 8, and nothing [on] days 15 to 21.”

For patients with identified tumor mutations, there are many clinical trials available. To find a clinical trial, providers can reference the National Library of Medicine’s ClinicalTrials.gov website for a list of studies actively recruiting participants.

As with pancreatic cancer, chemotherapy or radiation may be provided before surgery for borderline resectable tumors and as palliative treatment to shrink or slow tumor growth and provide symptom relief. Transplant candidates may also receive chemotherapy while awaiting surgery.

Understanding all treatment options available would be daunting, according to Wild. However, she believes that “the best nurses don’t know everything, but the best nurses know where to find resources.”

AE Management

AEs related to chemotherapy start quickly, whereas effects from immunotherapy can take weeks or even months to appear. “With immunotherapy, [adverse] effects include the itises,” Wild said. “T cells recognize the tumor and kick into action. The immune system may get too excited and exert action on healthy tissue.”

Immunotherapy symptoms have similar presentation to autoimmune diseases. The most dangerous adverse effects are gastrointestinal, including immunotoxic colitis. “Diarrhea starts out of nowhere and is copious. Durvalumab, however, is tolerated very well,” Wild explained. Skin rashes, itching, and blistering dermatitis are managed with topical steroids. Immunotoxic hepatitis would be indicated by elevated liver enzyme levels. Pneumonitis is another effect that patients may experience. Management of any immunotherapy adverse effect would be corticosteroid administration.

“It’s crucial for patients to understand the [adverse] effects of immunotherapy vs chemotherapy vs both,” Wild said. “If patients [receiving chemotherapy] develop a cough, they may [have neutropenia], and we should do viral panels. Immunotherapy will not tank the neutrophil count. It could be pneumonitis.” It is important to involve the clinician because a thorough symptom assessment and consideration of onset is needed. An itchy, red skin rash on day 5 of a cycle is likely related to chemotherapy. Patients with this symptom can be directed to use an over- the-counter hydrocortisone cream. They can also take a picture of the rash and send it to the clinic, and the rash will be evaluated at the next visit.

With immunotherapy, patients who call late into cycle 3 or 4 with a new rash are likely not experiencing a chemotherapy reaction. These patients should receive a quick workup. “Nurses need to know what immunotherapy symptoms look like and [manage] them expediently [because] they can escalate quickly and lead to hospitalization. It’s better to be safe than sorry,” Wild noted.

Patients may feel they are bothering clinicians and not call. Rone reminds patients, “We’re not going home with you. If you don’t tell us your trouble, we can’t help you.” Patients often think they are to have serious AEs before they call. However, not only will these effects be worse for them if they wait, it will be less work for the clinical team, and better for the patient, if issues are treated sooner. Although the spectrum of possible AEs is broad, the reality is that a patient will only have a few of them. Patients should feel welcome and safe to report the smallest things; problems can escalate quickly.

Neuropathy is another AE and can be temporary or permanent, and patients may have difficulty walking. Treatment may need to be reduced, stopped, and restarted, or switched to another agent. If the patient has a stent, they may develop cholangitis, an infection in the biliary tree. Nurses should be aware of this potential issue and look for it. Symptoms may include elevated bilirubin as well as fever, abdominal pain, and jaundice. Pancreatic insufficiency causes patients to eliminate nutrients with defecation. Stools may be yellow, terra-cotta–colored, or gray.

Investigating probable causes of symptoms in relation to treatment or disease progression can help clinicians respond appropriately. Just because a patient is receiving chemotherapy or immunotherapy does not mean they will not be sick from other illnesses. Rone noted that “oftentimes patients are not treated sufficiently in the [emergency department because] doctors may think the problem is an AE of cancer therapies. Don’t blame symptoms on chemotherapy without investigating.”

Care Considerations

Pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma are difficult diseases to manage. It’s important for nurses to keep the conversation going with patients about palliative or end-of-life care. Care should be individualized and based on patient needs, desires, health status, location, and response to treatment. Direct patients to reputable sources of information and support, such as NCCN, PanCAN, and the Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation. As research and advanced treatments continue to evolve, staying abreast of the latest developments will help clinicians serve their patients with the best of care—and a helping of hope.

References

- Cancer facts & figures 2023. American Cancer Society. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://bit.ly/3JkQCnB

- NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, version 2.2022. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf

- Understanding somatic genomic testing in people with metastatic or advanced cancer. Cancer.Net. March 3, 2022. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://bit.ly/3TqNzO3

- Biomarker testing for cancer treatment. National Cancer Institute. December 14, 2021. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://bit.ly/3ymJLDK

- Liquid biopsy: using DNA in blood to detect, track, and treat cancer. National Cancer Institute. November 8, 2017. Accessed March 8, 2023.https://bit.ly/3ZMSniK

- Treatment options. Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation. 2023. Accessed March 8, 2023.https://bit.ly/3myMtn2

- NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Hepatobiliary cancers, version 5.2022. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hepatobiliary.pdf

- Surgery for bile duct cancer. American Cancer Society. Updated July 3, 2018. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://bit.ly/41XpxOm

- FDA approves durvalumab for locally advanced or metastatic biliary tract cancer. FDA. September 2, 2022. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://bit.ly/3JJvNCD