Novel Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors, Bispecific Antibodies Become Clinical Mainstays in Melanoma Nursing

What are the implications of new approvals for oncology nurses specializing in melanoma?

Krista M. Rubin, MS, FNP-BC, RN

In the past year, relatlimab combined with nivolumab (Opdualag) entered the clinical landscape for the treatment of patients with advanced melanoma.1 Tebentafusp (Kimmtrak), a bispecific antibody, also gained approval from the FDA for patients with uveal melanomas.2 What are the implications of these approvals for oncology nurses specializing in melanoma?

In an interview with Oncology Nursing News, Krista M. Rubin, MS, FNP-BC, RN, a nurse practitioner with the Center for Melanoma at Mass General Cancer Center in Boston, reflected on her experience integrating these agents into clinical practice and discussed what oncology nurses working in this setting need to know. Rubin is chair of the Melanoma Nursing Initiative and has been specializing in melanoma for the past 25 years.

As Rubin explained, surgical intervention is always preferred. For patients who remain high risk, even after surgery, adjuvant therapy is recommended to minimize the risk of relapse.

“Data from recent neoadjuvant clinical trials in patients with stage III melanoma have shown promising results and may lead to yet another paradigm shift in the management of advanced melanoma,” according to Rubin. “The idea is that administering immunotherapy prior to surgical resection enables a more effective antitumor response. Furthermore, this approach allows for the pathologic evaluation of treatment response, which in turn provides additional information about the biology of the tumor and the opportunity to modify treatment recommendations.”

For those who will therefore require systemic treatments, it is important that their nursing team know what to expect with these newly approved therapies and how to remain vigilant in identifying and reporting any associated adverse effects (AEs).

Relatlimab and Nivolumab

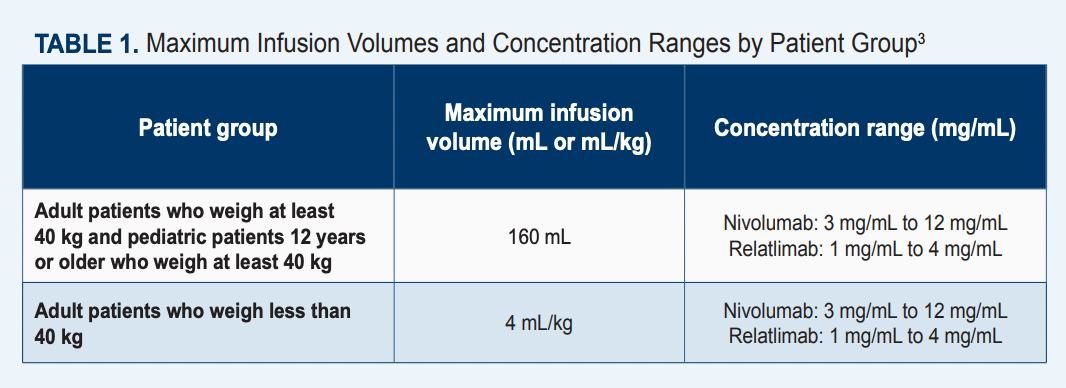

The FDA granted approval for the fixed-dose combination of relatlimab, a novel immune checkpoint inhibitor, plus nivolumab (Opdivo) in March 2022 for patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma who are at least 12 years of age and who weigh at least 40 kg (Table 13).1 The approval was supported by findings from the pivotal phase 2/3 RELATIVITY-047 trial (NCT03470922), which showed an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in patients who received the combination vs patients who received nivolumab alone. Data from this trial indicated that the median PFS with the combination was 10.12 months (95% CI, 6.37-15.74) vs 4.63 months (95% CI, 3.38- 5.62) with monotherapy, resulting in an HR of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.62-0.92; P = .0055). Moreover, at a 12-month follow-up, the PFS rates with relatlimab plus nivolumab (n = 355) were 47.7% vs 36.0% with single-agent immunotherapy (n = 359).4 In a final overall survival (OS) analysis, the median OS with relatlimab plus nivolumab was not reached (NR; 95% CI, 34.2-NR) vs 34.1 months (95% CI, 25.2-NR) with nivolumab alone. This resulted in an HR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.64-1.01).3

Rubin noted that many patients in her practice are receiving this treatment. She explained that for patients with advanced melanoma, treatment selection is based on a number of factors—including efficacy, toxicity profile, comorbidities, and patient preference. However, frontline treatment with combination immunotherapy is generally the preferred choice, either ipilimumab (Yervoy)/nivolumab or relatlimab/nivolumab.

Relatlimab/nivolumab is often selected for patients who are frailer or who do not show signs of aggressive metastases, according to Rubin. She added that it is a good option for patients who can handle something stronger than single-agent PD-L1 therapy but for whom ipilimumab/nivolumab may yield too strong a toxicity.

“For example, for a patient who presents with widely metastatic disease and is very symptomatic, we will be more likely to utilize ipilimumab/nivolumab because of the higher likelihood of response,” she explained. “However that comes with a high risk [56%] of developing toxicity severe enough to require urgent intervention, and often hospitalization, and treatment with a high dose of immunosuppresive medications,” she explained.

“I think of nivolumab/relatlimab as ‘kinder and gentler.’ Response rates are somewhat lower, but notably, the risk of high-grade toxicity is also lower [approximately 19%]. This is a frontline choice for patients with limited disease and/or those who are asymptomatic or minimally symptomat, whereas monotherapy with anti–PD-1 [nivolumab or pembrolizumab (Keytruda)] is the least likely to cause high-grade toxicity [approximately 10%] but also has the lowest response rates.

“For patients who have central nervous system [CNS] involvement, ipilimumab/ nivolumab is recommended, as it has proven activity in the CNS. At this time, activity in the CNS with relatlimab/ nivolumab is unknown.”5

In administering nivolumab/relatlimab, it is important to note that it is a fixed-dose combination and given as a single infusion. The recommended dose is 480 mg nivolumab/160 mg relatlimab every 4 weeks for the approved population. The recommended dose for alternative populations has not yet been established.3

“It is 240 mg of nivolumab plus 80 mg of relatlimab per vial,” Rubin emphasized. “So patients receive 2 vials, which is a total of 480 mg of nivolumab and 160 mg of relatlimab.”

Although the toxicity profile of relatlimab alone is unknown, no new safety signals have been observed with the agent, and the combination has exhibited behavior similar to that of other immunotherapies.3

“If you know how to manage nivolumab, you will know how to manage patients receiving the LAG-3 combination,” Rubin said. Key clinical pearls when caring for patients receiving this treatment include remaining vigilant for potential immune-related AEs [irAEs], she explained. Nurses should be aware that the combination may yield a higher toxicity profile than that of single-agent nivolumab, but lower than ipilimumab/ nivolumab, making it almost a middle-of-the-road regimen in terms of toxicity assessment and management. She also noted that, in her personal practice, gastrointestinal effects, hepatitis, diarrhea, colitis and endocrine dysfunction—specifically, thyroiditis—are some of the most common AEs that she has seen.

“There were no new toxicities identified with this combination, but oncology nurses should remain vigilant in looking for irAEs. And, if in doubt, everything is immune-related toxicity unless proved otherwise,” she said.

In addition, Rubin noted that certain AEs, such as cardiac or neuromuscular toxicities, appear to be more prominent with combination therapies than with single agent anti– PD-1 inhibitors. Therefore, she stressed that it is a good idea to get baseline testing done.

“In our practice, we check a baseline troponin and obtain a pretreatment EKG for all patients starting combination immunotherapy,” she said. “In our experience, it has been very beneficial to have those pretreatment assessments before launching into combination immunotherapy.”

Tebentafusp

Rubin also touched on the approval of tebentafusp for uveal melanoma—a type of melanoma that has seen relatively little progress in treatment options. Uveal melanoma is extremely rare, but Rubin has experience with this patient population, as her institution collaborates with Mass Eye and Ear to care for patients with ocular melanoma. Tebentafusp, a bispecific gp100 peptideHLA-directed CD3 T-cell engager, received FDA approval on January 25, 2022. Its indication is for adult patients with unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma who are HLA-A*02:01-positive. Tebentafusp is unique because it represents the first approved systemic therapy to treat unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma.2

“Tebentafusp targets tumor cells that express gp100 presented by HLA-A*02:01. Therefore, HLA testing is required to verify A2 subtype,” Rubin said. “Only patients who are HLA-A*02:01 positive are therefore eligible to receive this treatment; patients must be HLA-A*02:01-positive to present the gp100 peptide.”

The approval was supported by data from the phase 2 IMCgp100-202 trial (NCT03070392). Findings from the trial demonstrated that patients who received tebentafusp (n = 252) achieved superior OS rates at 1 year of follow-up compared with those who received investigators’ choice of therapy (n = 126; pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, or dacarbazine). The median OS between the experimental and control cohorts, respectively, was 21.7 months (95% CI, 18.6-28.6) vs 16.0 months (95% CI, 9.7-18.4), with an HR of 0.51 (95% CI, 0.37- 0.71; P < .0001).6 The most common grade 3 or worse AEs included rash (18%), pyrexia (4%), and pruritus (5%).

Tebentafusp is delivered intravenously (IV). Although it is administered in the outpatient setting, patients are admitted overnight for observation. This is because the greatest AE of interest with this drug is cytokine release syndrome (CRS), Rubin said. The drug’s prescribing label comes with a boxed warning for CRS.6 Approximately 1% of patients in the trial experienced grade 3 CRS, which was reported to be well managed. Manifestations for CRS can include fever, hypotension, hypoxia, chills, nausea, vomiting, rash, elevated transaminases, fatigue, and headache. Immediate access to medications and resuscitative equipment is crucial for managing CRS. Patients should be euvolemic prior to beginning any infusions. Furthermore, patients should be monitored for fluid status, vital signs, and oxygen levels. In the event of persistent and severe CRS, tebentafusp should be withheld or discontinued.

“After this drug is given, you can have this incredible storm of cytokines,” Rubin explained. “Cytokines are a component of the immune system that are activated when we have an [illness such as the] flu—we feel awful because cytokines have been released in an effort to deal with whatever virus or bacteria that we are fighting. When cytokines are ‘doing their thing,’ patients are at risk for hypotension, hypoxia, and different AEs like that.”

Most patients will develop some form of CRS that is typically manageable with supportive care such as IV fluids, acetaminophen, diphenhydramine, antiitch lotions or medications, and other symptom-directed care, she said. Rarely, severe CRS may require administration of the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab. However, according to Rubin, patients tend to do well with this treatment with proactive and close monitoring.

In addition, skin reactions and elevated liver enzymes should be monitored.6 Patients should receive antihistamines and topical or systematic steroids if skin reactions occur. Clinicians are advised to monitor alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and total blood bilirubin levels prior to the start of and throughout treatment to watch for elevated liver enzymes.

One of the other most common AEs is rash, which can be managed with moisturizers, topical steroids, and oral antihistamines. Some patients will experience what Rubin described as relatively predictable AEs, including rigors, chills, and fevers. Best practice is to provide supportive care, which can include the administration of oxygen or fluids, she said.

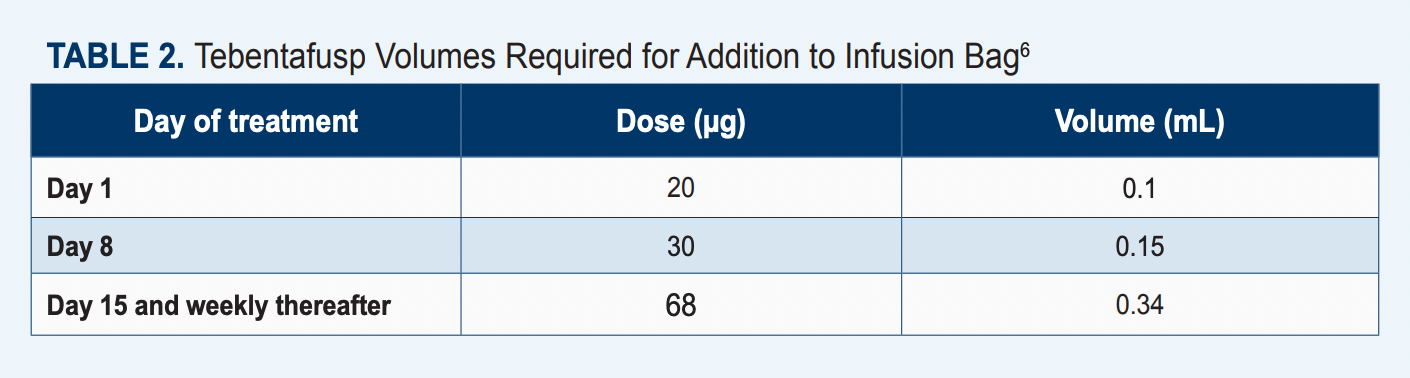

The recommended dose for tebentafusp is 20 µg on day 1, 30 µg on day 8, 68 µg on day 15, and 68 µg once every other week thereafter (Table 26). The agent should be diluted and administered via an IV infusion for approximately 15 to 20 minutes. Patients should receive tebentafusp in the inpatient setting for their first 3 infusions and be monitored for at least 16 hours following infusion completion.6

If the patient does not experience grade 2 or worse hypotension during or after the third infusion, subsequent doses may be administered in the ambulatory care setting, and the patient will need to be monitored for approximately 30 minutes or more after each of these infusions.6

Of note, this agent is given with a ramp-up dosing schedule.6

“Depending on how patients do [with the first dose], you can somewhat predict how to best manage them for the next week,” Rubin said. “For example, if a patient comes in and, with the 20-mcg dose, they develop a significant rash, for the next dose we may increase their antihistamines by a dose or by strength to minimize the effect.”

Once a patient has successfully completed 3 weeks of treatment with tebentafusp, and they are doing well, they are able to be treated in the outpatient setting; the risk of CRS decreases once their body becomes accustomed to the treatment, she explained. Also, by the third week, both the patient and nursing care team are able to identify which effects to expect with treatment and select the best management strategies.

“Once you learn what works for the patient, you’re able to adjust accordingly,” Rubin noted. “For oncology nurses, it’s ideal if the same nurse or nurses are taking care of the patient because then you get to know how they do with their weekly treatments.”

Nurses can also help patients optimize at-home education or care. For example, if patients live by themselves, and need help applying moisturizers or topical steroids, the nursing team can play a large role in brainstorming solutions.

“It’s a relatively predictable treatment; it sounds like a big deal, because there is this risk of CRS, and there is a lot that goes into it. But just like any patient who’s having, [for example], a bone marrow transplant or CAR [chimeric antigen receptor] T-cell therapy, there is kind of a realm of what you can expect that you generally follow.”

Not all patients will benefit from tebentafusp, but those who do can continue to receive a weekly dose indefinitely. By the fourth or fifth dose, they can expect very minimal AEs, she added.

Trajectory of Melanoma Research

Moving forward, melanoma treatments will become more concise, Rubin said.

“We are continuing to refine delivery of these agents; we are looking at things [such as] biomarkers to try to predict who may do well in terms of efficacy of these agents,” she said. Rubin also noted that there is a major focus on research in the neoadjuvant space, which could become more commonplace than adjuvant therapy.

“Can we give neoadjuvant [immunotherapy] and have a much greater outcome?” she reflected. “Or are you better off giving adjuvant therapy, knowing that there is a risk of long-term toxicity for a population of patients [who] may not have needed treatment? That’s always the consideration.”

References

- US Food and Drug Administration approves first LAG-3-blocking antibody combination, Opdualag (nivolumab and relatlimab-rmbw), as treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma. News release. Bristol Myers Squibb; March 18, 2022. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://bit.ly/3wk6PDx

- FDA approves tebentafusp-tebn for unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma. FDA. Updated January 26, 2022. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://bit.ly/3K5Dfqw

- Opdualag. Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2022. https://bit.ly/43Gp8Ry

- Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ, et al; RELATIVITY-047 Investigators. Relatlimab and nivolumab versus nivolumab in untreated advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(1):24-34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2109970

- Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Algazi A, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in melanoma metastatic to the brain. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(8):722-730. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1805453

- Kimmtrak. Prescribing information. Immunocore Commercial LLC; 2022. https://bit.ly/3ohWkP8

Cemiplimab as Adjuvant Therapy Improves DFS in High-Risk Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

January 20th 2025Adjuvant cemiplimab demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in DFS compared to placebo in post-surgical patients with high-risk CSCC, impacting post-operative care considerations.