Rusfertide Helps Combat Iron Deficiency and Improve Symptoms in Patients with Polycythemia Vera

Symptomatic iron deficiency, a key challenge in facing polycythemia vera, might be effectively treated with rusfertide.

Rusfertide (PTG-300) has proven to be effective in reversing iron deficiency, improving disease-related symptoms, and erasing the need for therapeutic phlebotomy, making it a quality option for patients with polycythemia vera (PV).1

“The rate of phlebotomies was very high in this heavily phlebotomy-dependent patient population prior to initiation of therapy. As soon as patients initiated treatment with rusfertide, the rate of phlebotomy decreased dramatically [P <.0001],” said Marina Kremyanskaya, MD, PhD, lead study author and assistant professor of medicine, hematology, and oncology at Mount Sinai Hospital, in a presentation on the data. “Most of the patients who required phlebotomy during this period were in the dose-saturation phase of the trial and needed a higher dose.”

Moreover, hematocrit and red blood cell count in patients with PV continued to be well controlled throughout the study, according to Kremyanskaya. No significant change in platelets or white blood cell count was observed. Notably, at the beginning of the study, all patients had very low ferritin. As the study continued, ferritin levels steadily increased, demonstrative of improvement in iron deficiency with the study drug.

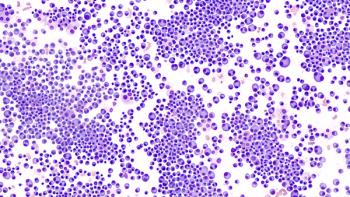

PV is characterized by the increased production of red blood cells and a higher risk of thrombosis; this population is treated with periodic phlebotomy with or without cytoreductive therapy. These patients are known spend significant time with hematocrit levels of greater than 45%, thereby potentially increasing their risk of thrombosis.2

Often, patients with polycythemia vera have iron deficiency at the time of diagnosis and receiving several phlebotomies can worsen this condition. As such, symptomatic iron deficiency signifies a key challenge faced with this disease.

However, investigators have postulated that iron deficiency and expanded erythropoiesis in PV can result in hepcidin suppression and that this suppression could serve to strengthen iron availability for erythropoiesis in this patient population. To this end, the phase 2 PTG-300-04 trial was launched to evaluate the hepcidin mimetic rusfertide in phlebotomy-dependent patients with PV.

“In the setting of polycythemia vera, hepcidin is low. Therefore, ferroportin is open, thus allowing iron to freely flow into the plasma, making it available…in the bone marrow and resulting in uncontrolled erythropoiesis and high hematocrit,” Kremyanskaya explained. “In the presence of rusfertide, ferroportin is closed, and therefore, iron is not available to freely flow into the plasma; this limits the amount of iron that is available for erythropoiesis and results in hematocrit control.”

In June 2021, the FDA granted a breakthrough therapy designation to rusfertide for the treatment of patients with PV for the reduction of erythrocytosis in those patients who do not require further treatment for thrombocytosis and/or leukocytosis.3 The decision is supported by data from the ongoing phase 2 trial that was presented at the ongoing congress.

The phase 2 study enrolled patients with PV as per 2016 World Health Organization criteria and at least 3 phlebotomies with or without concurrent cytoreductive therapy in the 6 months prior to the trial. Rusfertide was subcutaneously administered at doses of 10 mg to 80 mg on a weekly basis in addition to previous standard therapy.

The primary end point of the trial was the proportion of patients in the randomized withdrawal period whose hematocrit is maintained without the need for phlebotomy.

The trial is comprised of 3 parts. In the dose-finding phase of the trial, patients were started on a low dose of rusfertide, which was titrated every 4 weeks to control the hematocrit at less than 45%. Once the effective dose of the agent was determined, patients remained on the dose until 28 weeks.

Then, they entered the blinded withdrawal phase of the trial where they were randomized to continue on their last effective dose or to receive placebo. If the patient required a therapeutic phlebotomy at any point in this phase of the trial, they were withdrawn and entered into the open-label extension phase of the research. Here, they were restarted on their last effective dose of rusfertide.

At the time of the presentation, 63 patients with PV had been dosed with rusfertide, duration of exposure ranged from 2 to 81 weeks, and the median exposure to treatment was 15 weeks.

The median age of study participants was 56 years (range, 27-76), 72.6% were male, 48.4% were in the low-risk category, and 14.5% of patients had prior thrombotic events. Additionally, 55% of patients had a diagnosis of PV for 3 years or less.

Just under half, or 46.8%, of patients received phlebotomy only and the remainder received phlebotomy with another cytoreductive agent such as hydroxyurea (29%), interferon (14.5%), and ruxolitinib (Jakafi; 4.8%). In the 6 months before the trial, 46.8% of patients had received 4 to 5 phlebotomies. Sixty-eight percent of patients had an allele burden of less than 60%.

Investigators also examined symptom scores, as demonstrated by the MPN Symptom Assessment Form Total Symptom Score. Results revealed a decrease in total symptom score at week 28 of treatment vs baseline. “This was mostly contributed to by the symptoms of fatigue and problems with concentration, with some contribution from pruritus,” Kremyanskaya said. “These data are still preliminary, as the number of patients with available data at week 28 is still relatively small.”

When looking at the patient global impression of change, 71% of patients experienced an improvement at 9 weeks of treatment, with most patients reporting to have been much improved and very much improved.

Regarding safety, rusfertide was found to be very well tolerated, according to Kremyanskaya. The majority of treatment-related adverse effects (AEs) were grade 1 or 2 in severity. Two grade 3 AEs were reported, but were not determined to be associated with the drug; 1 patient experienced vomiting and the other experienced distal popliteal artery aneurysm and both continued the drug. No grade 4 toxicities were reported.

The most common toxicities were injection site reactions and were linked with 28.1% of injections. All of these reactions were transient and none of the patients discontinued because of these effects. Notably, no serious AEs related to rusfertide were reported, and only 1 patient discontinued treatment because of toxicity, which was thrombocytosis. No anti-drug-antibody response was observed in any patient.

“These results provide additional evidence that rusfertide may have a clinical benefit for patients with polycythemia vera,” Ronald Hoffman, MD, the Albert A. and Vera G. List Professor of Medicine and director of the Myeloproliferative Disorders Research Program at Mount Sinai, stated in a press release on the data.4 “The need for a new non-cytoreductive therapeutic option in polycythemia vera is urgent. I look forward to the next steps in rusfertide’s development for this disease, as it may alleviate the burden of phlebotomy for patients who cannot control their hematocrit levels through currently existing treatment options and need an alternative therapeutic approach.”

References

- Kremyanskaya M, Ginzburg Y, Kuykendall A, et al. PTG-300 eliminates the need for therapeutic phlebotomy and reverses iron deficiency in both low and high-risk polycythemia vera patients. Presented at: European Hematology Association 2021 Virtual Congress; June 9-17, 2021; virtual. Abstract S200.

- Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):22-33. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208500

- Protagonist Therapeutics receives FDA breakthrough therapy designation for rusfertide in polycythemia vera. News release. Protagonist Therapeutics. June 3, 2021. Accessed June 12, 2021.

https://bit.ly/3pMfKYO - Protagonist Therapeutics announces updated phase 2 data supporting long-term efficacy of rusfertide in polycythemia vera. News release. Protagonist Therapeutics. June 11, 2021. Accessed June 11, 2021.

https://prn.to/3wkqNel

Newsletter

Knowledge is power. Don’t miss the most recent breakthroughs in cancer care.