Guest Blog: Example of a Case Impacted by the Help-Hurt Tool

Ms. M is an 81-year-old woman with Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer. She had remained in great health until her recent diagnosis, after which her energy had plummeted and she was spending over half the day in bed. Overwhelmed with the sight of their loved one losing her strength with each passing day, her family had gone into panic. “Chemotherapy has helped so many, right?” “Couldn’t the doctors save her from this cancer?” “We need to try something, doctor!”

The patient herself was detached from the idea of battling the disease: “I have lived a good life,” she would say, and take a passive stance in her illness. This attitude further distressed the family: “it is like she is giving up.” Upon request of the family, an oncologist evaluated the patient and took the time to discuss treatment options. Surgery was no longer an option, and radiotherapy was not going to be particularly useful. The only remaining option was chemotherapy.

Patient and family were in the dark in regards to what chemotherapy really meant. An informative pamphlet on one of the potential chemotherapeutic drugs to be used made things even more confusing. “Nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, rash, edema, gastrointestinal bleed…” This family system soon found itself in hours-long lock-down discussions: “chemotherapy is going to make her suffer more!”, “she is not going to give up like this!”, “if not chemotherapy then what?!”, “what if chemotherapy saves her life?!”

The Help-Hurt Tool

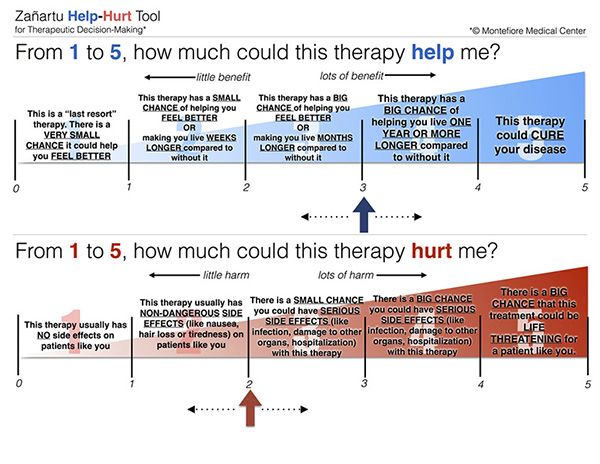

The Help-Hurt Tool, courtesy of Montefiore Medical Center

Finally, a family discussion was held in the presence of an oncologist and palliative medicine consultant with the use of theHelp-Hurt tool (HHT). Needless to say, the patient was there as well, since she is the primary decision maker. The option of a particular chemotherapy drug used for these situations was evaluated with the use of the HHT. This particular drug—Gemcitabine, that would be given in an infusion—was aimed at trying to keep the tumor from advancing and causing more discomfort, and eventually cutting the patient’s life shorter.

When the patient and family were presented with the HHT and explained its rationale, one of the relatives’ first reaction was to point at the Help score 5 (“This therapy could cure your disease”) and say: “this one doc, we want this one.” With calm, compassion, and honesty, it was explained to the patient and family, with the graphic example of the HHT, that “cure”-achieving-chemotherapy was not an option. The drug suggested would likely give a Help score of 3 (prolongation of life by a matter of months) and Hurt score of likely 4 (big chance of these serious side effects) since the patient at this point was too debilitated to sustain a strong chemotherapy regimen.

When presented with the contrast of the Help and Hurt scores, the family became more aware of the limited benefit of a course of chemotherapy and the likelihood of side effects. After a week to ponder, family and patient concluded in unison to avoid chemotherapy all together and focus on family time and comfort. None of the family members were left with a sense of “failure” or “abandonment” to their loved one. It was clear to them that they were not saying “no” to a life-saving procedure. They were saying “yes” to their loved one’s autonomy and to a peaceful time together.

Multidisciplinary Training of BiTE-Associated AEs Increases Safety in Outpatient Setting

April 13th 2025Authors noted that BiTEs have expanded the treatment paradigms for several types of solid tumors and blood cancers; however, toxicities associated with this class of agents have raised safety concerns.