Computerized Training May Ease Cognitive Impairment in Cancer Survivors

An at-home computerized program could be beneficial in treating cognitive impairment in cancer survivors.

Cognitive impairment — commonly referred to as “chemobrain,” in those who received chemotherapy – is a persistent problem that many cancer survivors face. Despite its prevalence, there is limited research as to why it occurs or how it can be managed or prevented.

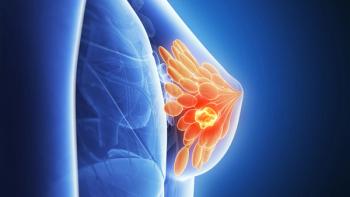

In an attempt to fill this gap, researchers from Indiana University School of Nursing investigated whether home-based computerized cognitive training modules could improve attention control in breast cancer survivors.

“If you’ve taken care of breast cancer survivors, you know that oftentimes they have lingering symptoms,” said Diane Von Ah, PhD, RN, FAAN, Community and Health Systems chair and associate professor at the Indiana University School of Nursing. She also mentioned that 75% of the 2.6 million breast cancer survivors report some kind of cognitive dysfunction.1

Von Ah presented her team’s findings at the 2019 Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) 44th Annual Congress in Anaheim, CA.

Sixty-eight breast cancer survivors were randomized to receive either computerized cognitive training through a program called BrainHQ, or attention control. Eligible participants were female; had non-metastatic breast cancer; were 21 years of age or older; had completed their last chemotherapy treatment at least 1 year earlier; reported memory impairment; and spoke English. Each participant (both in the intervention and control arm) participated in 40 hours of their respective online activity over an 8-week period.

The BrainHQ program aims to improve visual processing speed, learning, memory, and attention. It includes activities that involve time-order judgement, discrimination, spatial-match, forward-span, instruction-following, and narrative memory tasks. The attention control group participated in online activities that are commonly believed to improve memory and cognitive function, such as puzzles, sudoku, crosswords, etc.

Data was collected at baseline prior to the intervention and immediately after the intervention, which was 10 weeks long.

Multiple aspects were examined:

- Feasibility and satisfaction, measured by study adherence and completion rates

- Self-reported data, where participants reported on facilitators, barriers, and perceived satisfaction

- Cognitive performance, which was assessed through objective neuropsychological tests

- Perceived cognitive function and symptoms, which was measured through self-assessed measures including depressive symptoms, anxiety, and fatigue

- Perceived work ability and quality of life

Interestingly, preliminary results showed that there was no difference found between the 2 groups when it came to satisfaction and feasibility. In the intervention arm, there was a self-reported 24.91 average satisfaction score, versus 23.63 in the attention control.

“This shows us that they felt that the attention control was acceptable and satisfying,” Von Ah said.

When it came to immediate recall (measured using the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test or RAVLT), scores for the intervention arm increased from an average of 10.27 to 11.73, while the control arm increased from 10.44 to 12.56. For delayed recall (also measured using the RAVLT), the BrainHQ arm had an average of 9.64 at baseline, which increased to 10.82 post-intervention. For the attention control arm, the mean went from 10.00 to 11.89.

“We are starting to see that the intervention has a positive effect,” Von Ah said. “Currently there are no guidelines to treat [cognitive impairment], but computerized training may be promising.”

Reference

Von Ah D, Crouch A. Computerized Cognitive Training in Breast Cancer Survivors. Presented at: ONS 44th Annual Congress; April 11-14, 2019; Anaheim, CA.

Newsletter

Knowledge is power. Don’t miss the most recent breakthroughs in cancer care.